Monitoring ALD

Monitoring ALD

Cerebral ALD is a rapidly progressing, life-threatening disease that should be diagnosed as early as possible to help prevent irreversible brain damage.1-4 It involves the destruction of the myelin sheath that protects nerve cells in the brain.2 If left undiagnosed and untreated, the progression of cerebral ALD is rapid, causing severe loss of neurologic functions including loss of cognition, vision, hearing, and motor function. Ultimately cerebral ALD results in death.2,4

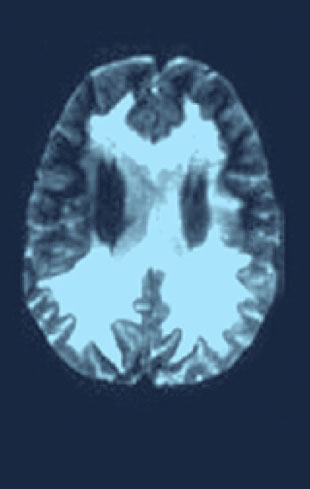

Regular MRI scans in boys diagnosed with ALD are critical to detect white matter changes indicative of progression to cerebral ALD.1

- White matter changes on MRI precede the onset of symptoms, so MRI monitoring is critical as it can detect progression to cerebral ALD before any symptoms arise.1

- Symptoms of progression to cerebral ALD may mimic conditions like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, or other home and school problems, which can delay diagnosis.1,5

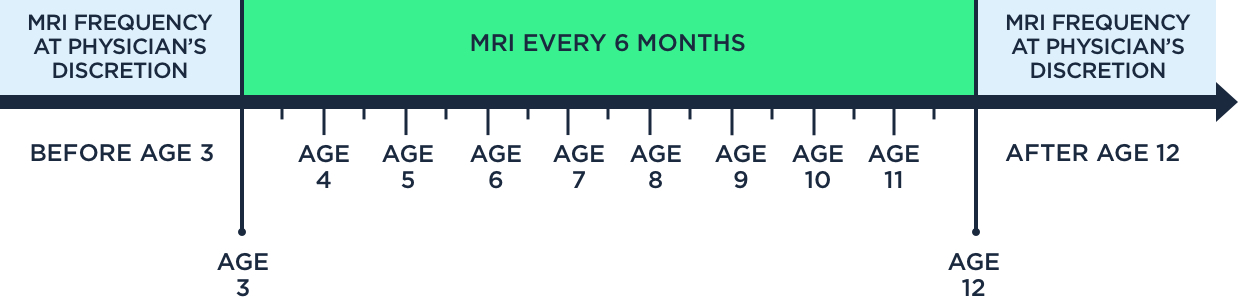

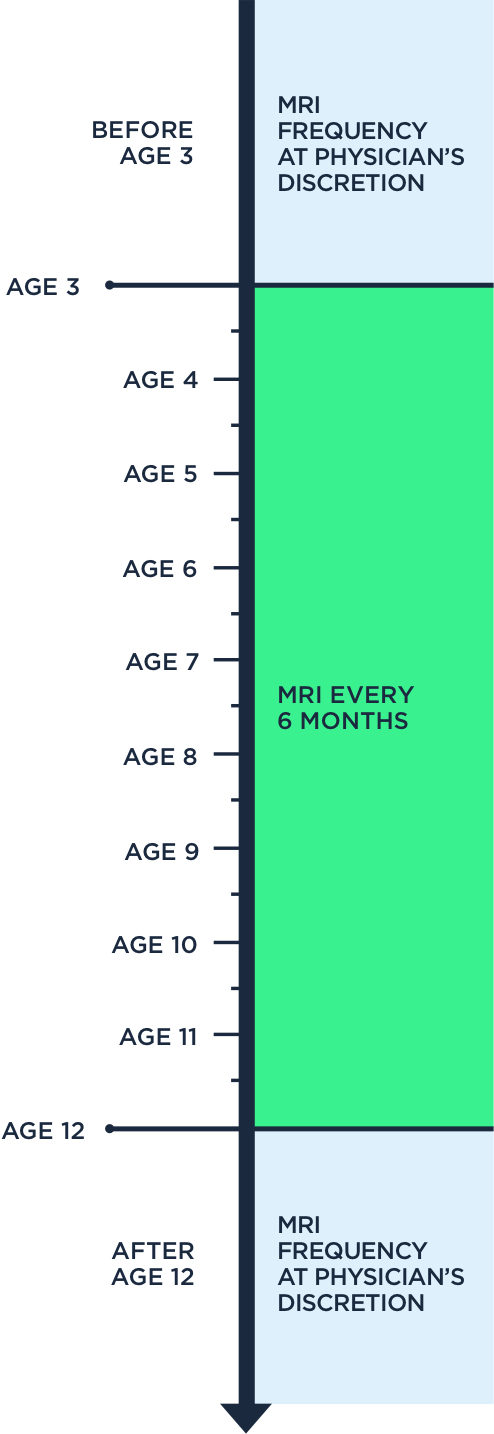

MRI SHOULD BE PERFORMED EVERY 6 MONTHS IN 3- TO 12-YEAR-OLD BOYS WITH ALD 2

MRI screening guidelines for signs of cerebral ALD

Since there is no way to predict which patients with ALD will progress to cerebral ALD, it is important to detect cerebral ALD via MRI as early as possible, as the disease can progress very rapidly.2,3

Brain changes detected through MRI precede the onset of clinical symptoms of cerebral ALD by months—once these symptoms develop, it is often too late to treat effectively because of the rapid progression of the disease.6

Monitoring for brain changes related to ALD involves an MRI about every 6 months through the critical window when they are at the highest likelihood of cerebral progression—this is crucial because identifying changes early can help us provide treatment.

Bradley Miller, MD, PhD Paediatric endocrinologist

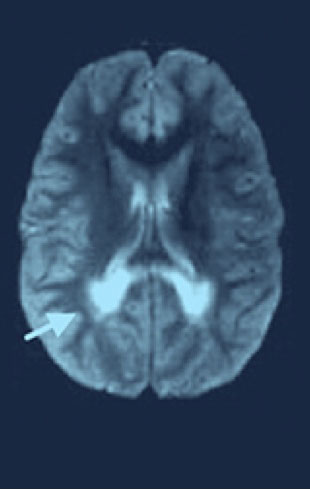

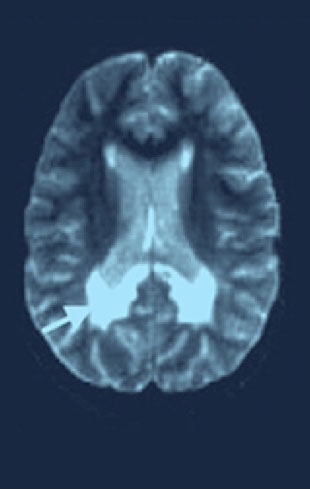

Reproduced with permission from Cartier N, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Bartholomae CC, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X‑linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326(5954):818-823.

INITIAL SYMPTOMS

- Poor school performance

- Behavioral problems

- May be misdiagnosed as ADHD

MODERATE DISABILITY

- Hearing

- Aphasia/apraxia

- Vision impairment

- Swallowing dysfunction

- Walking/running difficulties

- Episodes of incontinence

- Seizures

MAJOR FUNCTIONAL DISABILITY

- Cortical blindness

- Loss of communication

- Tube feeding

- Wheelchair dependence

- No voluntary movement

- Total incontinence

Early diagnosis of ALD, along with regular monitoring by a neurologist, can enable treatment before severe and irreversible brain damage occurs.1 Even in the absence of symptoms, regular MRI monitoring is critical, as scans may reveal abnormalities prior to the detection of any cognitive dysfunction.4 In elementary school–aged boys, early symptoms of cerebral ALD can include cognitive deficits and behavioral problems that may manifest as a decline in school performance.2,5

Monitor ALD with regular MRIs

Once a child has been diagnosed with ALD, it’s important that they see a neurologist for screening for brain changes that are part of the disease.1

Bradley Miller, MD, PhD Paediatric endocrinologist

Regular MRI monitoring is critical for detecting the progression to cerebral ALD1

After diagnosis, it’s important to work with an integrated team of physicians, including a pediatric endocrinologist, a neurologist, a metabolic and genetic specialist, and a transplant team, to carefully monitor and help detect any signs of progression to cerebral ALD.1 Each specialty brings unique expertise—explore the tabs below to learn more about the contributions of each team member.

Pediatric endocrinologists perform regular adrenal assessments, provide referrals to other specialists, and provide ongoing management and treatment of adrenal symptoms.7

Pediatric neurologists or metabolic disease specialists can offer specialized resources designed to help monitor and manage ALD.1,7

Neurologists can conduct vigilant MRI monitoring to help in timely identification of life-threatening cerebral ALD.1 If progression to cerebral ALD is detected, a neurologist can provide consultations on treatment, as well as broader access to specialized resources that can help boys and families manage ALD.1

Metabolic and genetic specialists coordinate care and provide genetic counseling and screening to the patient’s family.8

Transplant specialists provide consultations on treatment if tests indicate progression to cerebral ALD.1,9

An integrated care team can offer specialized resources designed to help manage ALD.1,7

An integrated care team can offer specialized resources designed to help manage ALD.1,7

Vigilant monitoring and early diagnosis can have a positive impact on clinical outcomes1

Early diagnosis of ALD, along with regular monitoring, can help neurologists initiate treatment before severe and irreversible brain damage occurs.1 If and when cerebral symptoms develop, it is critical that patients work together with their neurologist to determine next steps.1,2

IMPLEMENT A MRI MONITORING PLAN FOR YOUR PATIENT

If monitoring is not part of your normal care routine, refer your patient to a neurologist.

COLLABORATE WITH AN INTEGRATED MULTIDISCIPLINARY ALD HEALTH CARE TEAM

Comprehensive care involves several disciplines.

WORK WITH A BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT PHYSICIAN TO PLAN FOR TREATMENT IF NEEDED

Consult with a transplant physician early to ensure timely treatment—results are more favorable the earlier treatment is started.1

References: 1. Moser HW, Mahmood A, Raymond GV. X‑linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(3):140-151. 2. Engelen M, Kemp S, Poll-The BT. X‑linked adrenoleukodystrophy: pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14(10):486. 3. Bezman L, Moser AB, Raymond GV, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: incidence, new mutation rate, and results of extended family screening. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):512-517. 4. Miller WP, Rothman SM, Nascene D, et al. Outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for childhood cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy: the largest single-institution cohort report. Blood. 2011;118(7):1971-1978. 5. Kemp S, Huffnagel IC, Linthorst GE, Wanders RJ, Engelen M. Adrenoleukodystrophy – neuroendocrine pathogenesis and redefinition of natural history. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(10):606-615. 6. Liberato AP, Mallack EJ, Aziz-Bose R, et al. MRI brain lesions in asymptomatic boys with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Neurology. 2019;92(15):e1698-e1708. 7. Mahmood A, Dubey P, Moser HW, et al. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: therapeutic approaches to distinct phenotypes. Pediatr. Transplant. 2005;9 Suppl 7:55-62. 8. Haga, SB. Understanding Genetics: A New York, Mid-Atlantic Guide for Patients and Health Professionals. Washington, DC: Genetic Alliance, 2009 9. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The Transplant Team. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/learn/about-transplantation/the-transplant-team/

ALD Resources

ALD Resources